Waiora Te Ūkaipo – The Homeland

Written by: Hone Kouka

Directed by: Hone Kouka

The Opera House, 1st Mar 2026

Reviewed by: Tanya Piejus

This Aotearoa New Zealand Festival of the Arts sees the return of a powerful chronicle of the spiritual and cultural trauma of leaving home. Hone Kouka was commissioned to write Waiora Te Ūkaipo – The Homeland for the 1996 festival and its revival now is as deeply personal, emotionally affecting, and relevant as it was then. It’s become a landmark piece of Aotearoa New Zealand theatre exploring the impact of colonisation, urban drift, and the tension between past and future that feels prescient in the current political climate of this country.

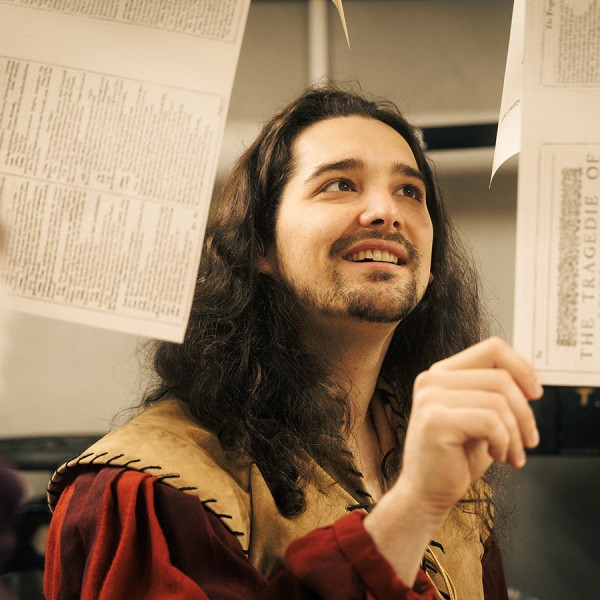

Set in the summer of 1965, the narrative concerns Hone (Regan Taylor) who has relocated his family from the East Cape to the South Island in search of a better life for them through his job at a sawmill. His wife Sue (Erina Daniels) holds everything together while older daughter Amiria (Rongopai Tickell) creates havoc and Boyboy (Te Mihi Potae) tries his best to please. As they gather near a beach for a birthday hāngi for their withdrawn youngest daughter Rongo (Tioreore Ngatai-Melbourne) with two Pākehā guests (Ben Ashby and Mycah Keall), secrets, heartbreak, and cultural tensions bubble to the surface and burst in ways that will ripple through their lives forever. Watching, responding to, and echoing the emotional ebb and flow of the day’s events are four tīpuna (Anatonio Te Maioha, Awerangi Thompson, Huia Rawiri, and Mathieu Boynton-Rata).

Working on Mark McEntyre’s cleverly sculptured set under Natasha James’ brilliantly responsive lighting design, this cast is electric. Their family dynamics are clearly communicated through sharp characterisations and their rendering of Kouka’s crackling dialogue. They particularly shine during the muscular waiata and haka (composer Hone Hurihanganui) that weave through the story to punctuate the emotional climaxes. Ngatai-Melbourne’s singing voice is sublime, and her thread of the story stitches the whole together until it profoundly squeezes the heart of its audience.

As Kouka stated before writing the play: “Everyone is from somewhere else.” Waiora Te Ūkaipo – The Homeland is for all who have ever felt dispossessed.