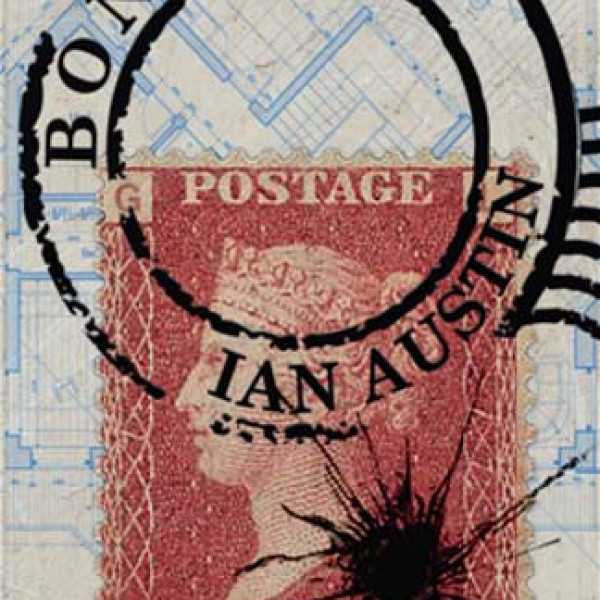

Year’s Best Aotearoa New Zealand Science Fiction & Fantasy III

Paper Road Press

Edited by Marie Hodgkinson

Reviewed by: Alessia Belsito-Riera

I was thoroughly impressed, entertained, and engaged by this collection. These authors are not only thought-provoking and self-reflective, but entertaining and wildly talented storytellers. Each piece is as intelligent and self-aware as it is poignant and cogitative. Both the fantasy and science fiction short stories push the boundaries of reality in order to create empathetic and compassionate literature that not only amuses but also forces the reader to evaluate their own choices, self, and reality.

Whether two pages or 10, direct or allegorical, each writing pushes the reader as part of a collective human race to think beyond ourselves and re-evaluate our position in the world at large, the world’s future, and our relation to other humans, other beings, and most urgently our relation to our planet. No matter the context each story is, in effect, both urgent and earnest in its appeal. The Waterfall by Renee Liang tackles politics, corruption, and bureaucracy during a near future environmental disaster where preserving political image through gaslighting is still prioritised over medical emergency. Both topical and demanding political accountability. Octavia Cade’s Otto Hahn Speaks to the Dead questions morality and the morality of violence versus self-violence during WWII. Florentina by Paul Veart comments on how clinically, animalistically, and uncompassionately humanity treats difference, while simultaneously reflecting on how this fear of difference forces often barbaric reactions to something like the AIDS epidemic or even our current COVID-19 pandemic. By painting pictures of post-apocalyptic futures, The Double-Cab Club by Tim Jones and The Turbine at the End of The World by James Rowland urge all of us to seriously acknowledge our imminent and impending environmental disaster.

Since reading this collection there are many stories that have crossed my mind daily but none as much as Casey Lucas’ For Want of Human Parts, which dissects, reconstructs, and assesses our own humanness and humaneness in the face of humanity itself.

The collection is pointed social commentary that forces us to look not only at ourselves as a society and human race, but also introspectively as individuals.