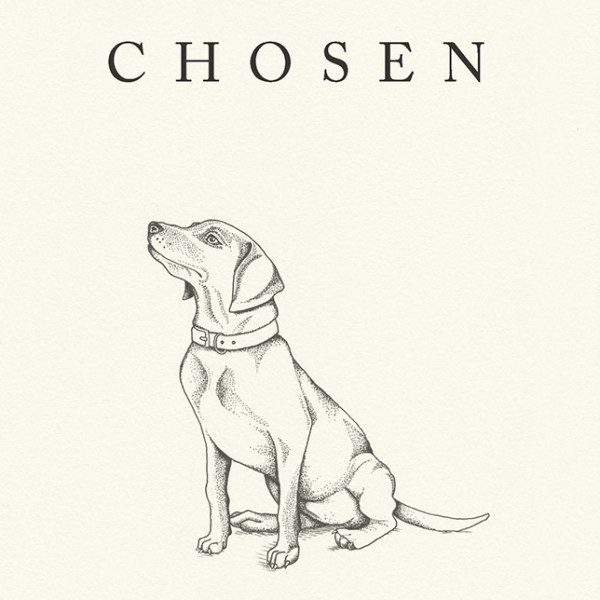

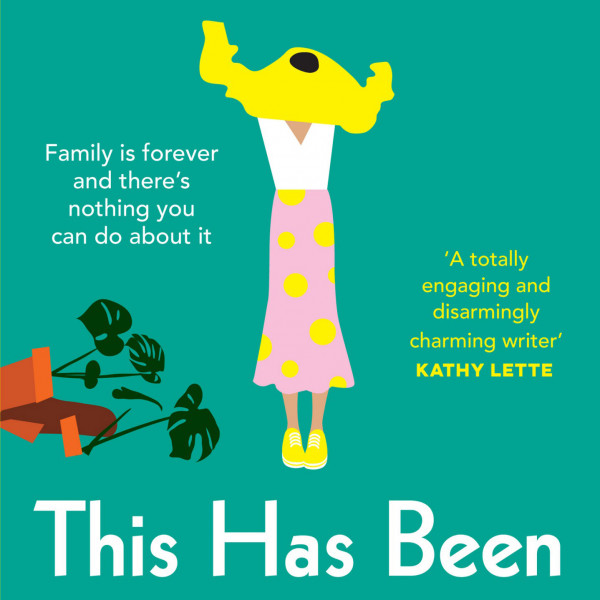

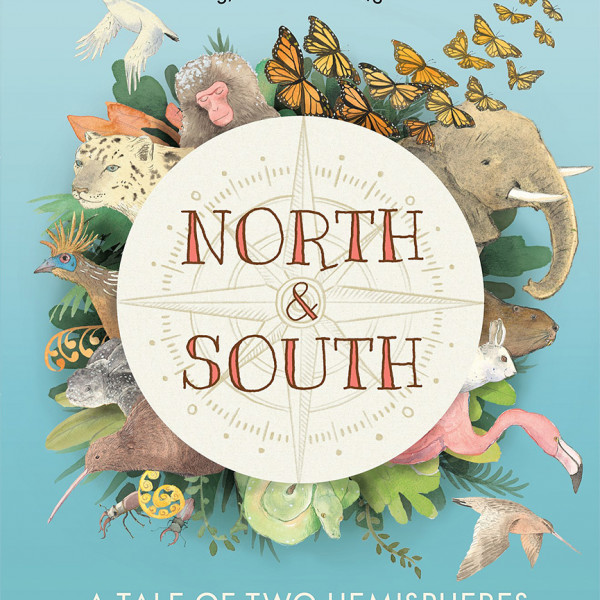

North & South: A Tale of Two Hemispheres

Written by: Sandra Morris

Walker Books

Illustrated by Sandra Morris

Reviewed by: Jo Lucre

North & South for me was a refreshing step away from a nightly reading selection heavily featuring robots, treehouses, a hybrid Dogman and flying furballs, and the never-ending speech bubbles that comics afford.

Author and illustrator Sandra Morris has written a delightful and picturesque introduction to the world we live in, the changing seasons, and the animals that coexist with us around the world.

It’s easy to use the book as a talking point about seasons and migration with some of the world’s most wondrous animals, who by their very existence adapt and adjust to the climate and inhabitants around them. The illustrations elevate the words beautifully and are evidence of the author’s many talents.

Most interesting to my eight-year-old was the hoatzin, otherwise known as a stinkbird, as it emits a smell like manure and regurgitates fermented plants to feed its hatchlings. From the pungent aroma of the hoatzin we quickly digressed to conversations about the lifecycle and how prey and predator are ever-changing depending on where you are in the food chain. The awful pungency of the hoatzin means the young chicks are at the mercy of capuchin monkeys, snakes, and birds who are attracted to the smell.

Morris has categorised the animals giving them each a conservation status. The polar bear, for instance, is deemed vulnerable, at high risk of extinction, whereas the green tree python is of low concern with a relatively low risk of extinction. There is a glossary and an index too that will help the most curious of minds to extend their knowledge and vocabulary.

Despite this, my son did become disengaged with the length of North & South and suggested that measurements to show how big the animals are in relation to humans would have been cool. Of course, I hadn’t thought of this, and was reminded how different the world is through a child’s lens and how reading North & South a little and often may just be the way to go.