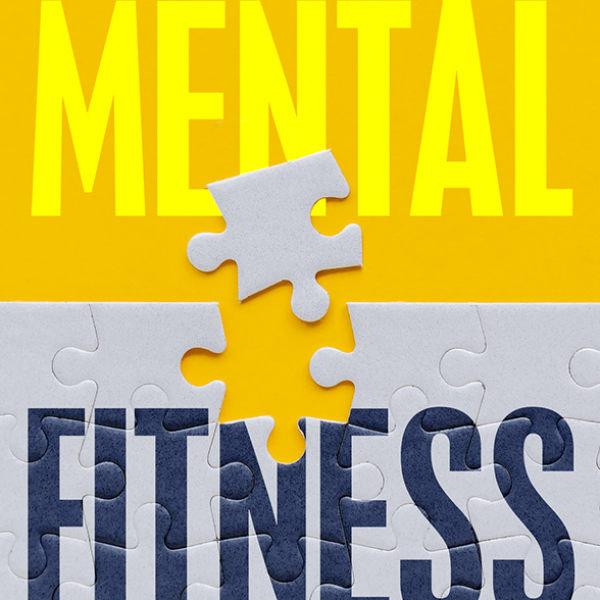

At the age of 18, Paul Wood was convicted of murder and served 11 years behind bars. While there, he managed to turn his life around by becoming the first person in New Zealand history to complete an undergraduate and master’s degree while in prison.

In his latest book, Dr Wood explains the term ‘mental fitness’ and why it is so important to strengthen it to help deal with the challenges we face every day. At the heart of the matter is the idea that mental fitness can be strengthened, just as a bodybuilder lifts weights to enhance physical fitness.

One of the biggest problems I have with most self-help books is that I’m always sceptical about the author’s motives and how much they really know about the topic they are writing about. But not this time; I mean, here is a man that was sent to prison, served time with some of the worst offenders in the country, and came out the other side a better, wiser person. In the case of Mental Fitness, there was no doubt in my mind that what I was reading was 100 percent genuine and that Wood was the real deal.

His writing too impressed me with what is sometimes called the ‘common touch’, that ability to connect with just about everyone and to make them understand the message you are trying to send. Mental Fitness is incredibly simple to understand and, as a result, an easy read. Nothing is too difficult to grasp, and nothing feels undoable for those who pick this up to improve themselves. There are really no downsides that I could find here, and I think this is something everyone should read at least once.

I really loved this book and will definitely be putting some of Dr Wood’s ideas into practise to increase my own mental fitness.