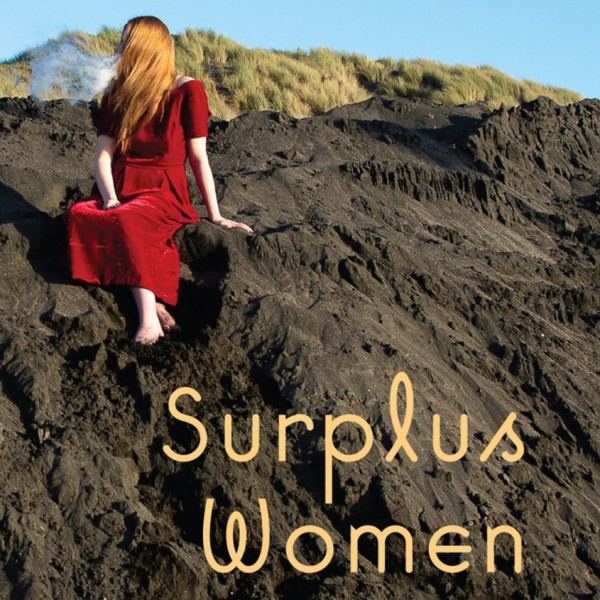

Julia Eichardt: A Life of Grit and Grace

Written by: Lauren Roche

Flying Books Publishing

Reviewed by: Kerry Lee

For everything that Julia Eichardt: A Life of Grit and Grace lacks in over-the-top action, it makes up for with one of the most fascinating books I have read lately.

From living an impoverished life helping her mother raise a struggling family in Ireland in the latter half of the 19th century, to the goldfields of Australia, and finally arriving in New Zealand in 1863 during the gold rush era, Julia Eichardt was a fascinating person with an amazing story. While most of Queenstown’s history is hogged by men, she was one of many women who helped make it what it is today. After working as a waitress and bartender, Julia went on to own and run her own hotel: Eichardt’s Private Hotel, which still stands today on Lake Wakatipu. In this historical novel, we read her journey from the very beginning and see the obstacles she faced as a woman in quite literally a man’s world.

I have always been fascinated by the past and the people who shaped it. Normally we only hear about politicians, or the wealthy who donated land and have a park or a street corner named after them. Very rarely do we hear about the lesser-known folks who collectively kept the busy towns and cities buzzing away, and when we do, we don’t tend to get an in-depth look into their lives like the one author Lauren Roche has provided here.

While this may not seem like a surprise to many, my favourite character in the entire book is Julia herself. Her determination was just so awe-inspiring that I had to pump my fist in the air every time she triumphed and overcame an obstacle. Against all the odds, she managed to achieve her dreams and build the grand hotel that she always wanted to.

She really was someone I began admiring and looking up to, and I think reading about her life could inspire others as well. That’s the power of books based on real people: they can help those who cannot see a way forward with their own problems.