Enigma

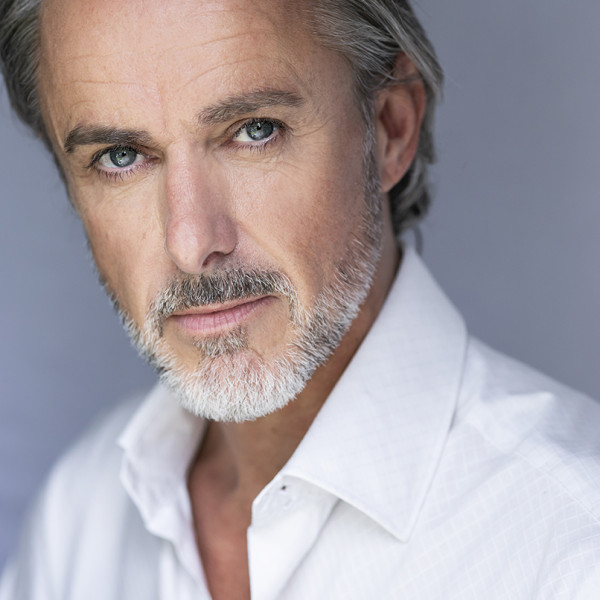

Presented by: New Zealand Symphony Orchestra

Conducted by: Edo de Waart

Michael Fowler Centre, 13th Apr 2019

Reviewed by: Dawn Brook

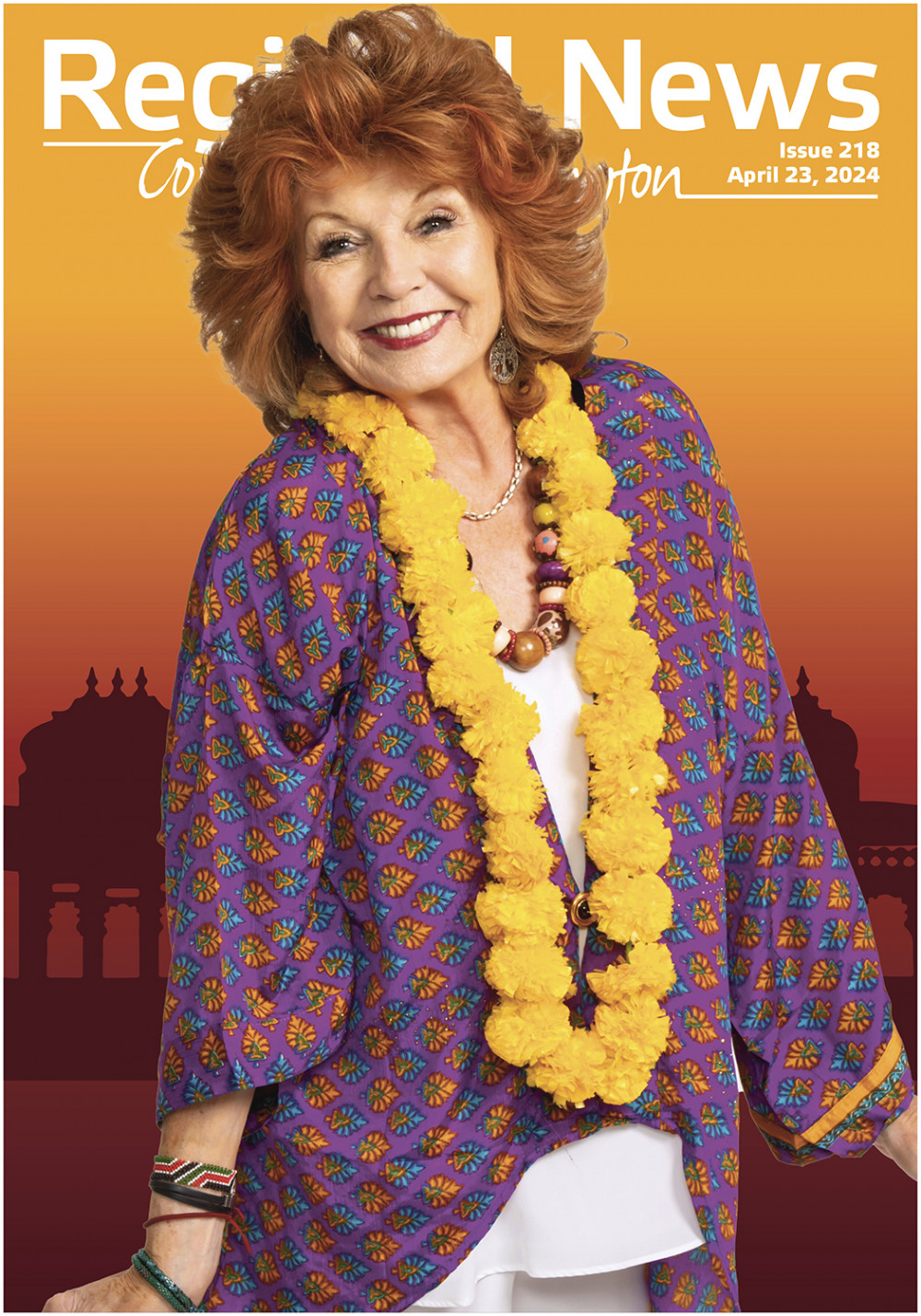

“My Concerto has had a brilliant and decisive – failure. At the conclusion three pairs of hands were brought together very slowly, whereupon a perfectly distinct hissing from all sides forbade any such demonstration”. So wrote Brahms after an early performance of his Piano Concerto No 1 in D Minor. The concerto has gone on to be an often-performed great favourite of the piano concerto repertoire. Joyce Yang as soloist and the NZSO amply demonstrated why to a capacity audience.

The first movement provides tremendous contrasts of majestic and lyrical themes, the second restrained reflectiveness, and the third urgent drive and rollicking momentum. Joyce Yang played with great commitment and intensity throughout, summoning simplicity and elegiac sweetness and thundering strength in turn, always with exquisite phrasing and within a wonderful partnership with the orchestra created by Brahms and Maestro de Waart.

The second work of the concert was a youthful one by Richard Strauss, Serenade for Winds in E flat major. It was good to see the NZSO’s excellent wind section profiled, though the work itself, while charming, was not the most riveting vehicle for doing so.

Maestro de Waart declared his love for Elgar’s music in the printed programme, and Elgar’s Enigma Variations was lovingly and gloriously delivered. Elgar composed the variations to provide musical images of himself and his wife, and 12 of his friends. The work has an engaging generosity of spirit and sunny optimism. He summons up a friend who produces cheerfully terrible piano playing, a friend’s daughter with a stutter, a beginner string player, a genteel lady, his publisher and long-term encourager whom he depicts with great warmth, and so on. This very English work is always stirring and the audience and orchestra will have gone away in very good humour, probably humming an Enigma theme.